Born : 23rd November, 1542 - Amarkot Fort, Sind

Died : 27th October, 1605 ( aged 63 ) - Fatehpur Sikri, Agra

Mogul ( Indian ) ruler

June 25, 1929 - Meherabad, India

Baba continued, "I like heroes such as Napoleon and Shivaji; they were never cowards. Napoleon was courageous till the last. Alexander the Great was brave, also. Emperor Akbar was brave, but not as brave as Shivaji. Even when the situation was hopeless, they did not run away. That is bravery. One must fight till the last, do or die!"

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (September 2009) |

| Akbar the Great | |

|---|---|

|

Mughal Emperor |

|

|

|

| Reign | 1556 to 1605 |

| Full name | Abu'l-Fath Jalal ud-din Muhammad Akbar I |

| Titles |

His Majesty Al-Sultan al-'Azam wal Khaqan al-Mukarram, Imam-i-'Adil, Sultan ul-Islam Kaffatt ul-Anam, Amir ul-Mu'minin, Khalifat ul-Muta'ali Sahib-i-Zaman, Padshah

Ghazi Zillu'llah ['Arsh-Ashyani], Emperor of India[1][2] |

| Born | 23 November 1542 |

| Birthplace |

Amarkot Fort, Sind |

| Died | 27 October 1605 (aged 63) |

| Place of death |

Fatehpur

Sikri, Agra |

| Buried |

Bihishtabad Sikandra, Agra |

| Predecessor |

Nasiruddin Humayun |

| Successor |

Nuruddin Salim Jahangir |

| Offspring | Jahangir, 5 other sons and 6 daughters |

| Royal House | House of Timur |

| Dynasty |

Mughal |

| Father |

Nasiruddin Humayun |

| Mother | Nawab Hamida Banu Begum Sahiba |

| Religious beliefs |

Islam,[3] Din i Ilahi |

Jalaluddin Muhammad

Akbar (جلال الدین محمد اکبر Jalāl ud-Dīn Muhammad Akbar), also known as

Akbar the

Great (November 23, 1542 – October 27, 1605) [1][2][4] was the third

Mughal Emperor of

India/Hindustan. He was of Timurid descent[5]; the son of Humayun,

and the grandson of Babur who founded the dynasty.

At the end of his reign in 1605 the Mughal empire covered most of Northern India.[6]

Akbar, widely considered the greatest of the Mughal emperors,[citation

needed] was thirteen years old when he ascended the throne in Delhi, following the death of his father Humayun.[7] During his reign, he

eliminated military threats from the Pashtun descendants of Sher Shah Suri, and at the Second Battle of Panipat he defeated the

Hindu king Hemu.[8][9] It took him nearly two more decades to consolidate his power and bring parts of northern and

central

India into his realm. The emperor solidified his rule by pursuing diplomacy with the powerful Rajput caste, and by admitting Rajput princesses in his harem.[8][10]

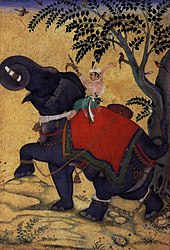

Akbar's reign significantly influenced art and culture in the region.[11] Akbar took a great interest in painting, and had the walls of his palaces adorned with murals. Besides encouraging the development of the Mughal school, he also

patronised the European style of painting. He was fond of literature, and had several Sanskrit works translated into Persian, apart from getting many Persian works illustrated by painters from his court.[11] He also commissioned many major buildings, and invented the first prefabricated homes.[12] Akbar began a series of religious debates where Muslim scholars would debate religious matters with Sikhs, Hindus, Cārvāka atheists and Portuguese Roman Catholic Jesuits. He founded a religious cult, the

Din-i-Ilahi (Divine

Faith), but it amounted only to a form of personality cult for Akbar, and quickly dissolved after his death.[8][13]

Contents |

Early years

Akbar was born on November 23, 1542 (the fourth day of Rajab, 949 AH), at the Rajput Fortress of Umerkot in Sindh (in modern day Pakistan), where Humayun and his recently wedded wife, Hamida Banu Begum were taking refuge[citation

needed]. Humayun gave the child the name he had heard in his dream at Lahore, Jalalu-d-din Muhammad Akbar [4][14] http://www.akbarattari.com

Humayun had been driven into exile in Persia by the Pashtun leader Sher Shah Suri.[15] Akbar did not go to Persia with his parents but grew up in the village of Mukundpur in Rewa (in present day Madhya Pradesh). Akbar and prince Ram Singh I, who later became the Maharaja of Rewa, grew up together and stayed close friends through life. Later, Akbar moved to the eastern parts of the Safavid Empire (now a part of Afghanistan) where he was raised by his uncle Askari. He spent his youth learning to hunt, run, and fight, but he never learned to read or write.[16] Nonetheless, Akbar matured into a well-informed ruler, with refined tastes in the arts, architecture, music and a love for literature.

Following the chaos over the succession of Sher Shah Suri's son Islam Shah, Humayun reconquered Delhi in 1555, leading an

army partly provided by his Persian ally Tahmasp I. A few months later, Humayun died. Akbar's guardian, Bairam Khan concealed the death in order to prepare for Akbar's succession.

Akbar succeeded Humayun on February 14, 1556, while in the midst of a war against Sikandar Shah to reclaim the Mughal throne. In Kalanaur, Punjab, the 13

year old Akbar donned a golden robe and Dark Tiara was enthroned by Bairam Khan on a newly constructed platform, which still stands.[17][18] He was proclaimed

Shahanshah (Persian for "King of Kings"). Bairam Khan ruled on his behalf until he came of age.[19][20]

The name Akbar

Akbar was originally named Badruddin Akbar, because he was born on the night of a badr (full moon)[citation needed]. After the capture of Kabul by Humayun his date of birth and name were changed to throw off evil sorcerers. [21] Contrary to some popular traditions, the name Akbar - meaning "Great" - was a not an honorific title given to Akbar; rather he was named for his maternal grandfather, Shaikh Ali Akbar Jami[citation needed].

Military achievements

Early conquests

Akbar decided early in his reign that he should eliminate the threat of Sher Shah's dynasty, and decided to lead an army against the strongest of the three, Sikandar Shah Suri, in the Punjab[citation needed]. He left Delhi under the regency of Tardi Baig Khan. Sikandar Shah Suri presented no major concern for Akbar, and often withdrew from territory as Akbar approached.[citation needed]

The Hindu king Hemu, however, commanding the Afghan forces, defeated the Mughal army and captured Delhi on 6 October 1556.[19] Tardi Beg Khan promptly fled the city. News of the capitulation of Delhi spread quickly to Akbar, and he was advised to withdraw to Kabul, which was relatively secure[citation needed]. But urged by Bairam Khan, Akbar marched on Delhi to reclaim it. Tardi Beg and his retreating troops joined the march, and also urged Akbar to retreat to Kabul, but he refused again. Later, Bairam Khan had the former regent executed for cowardice, though Abul Fazl and Jahangir both record[where?] that they believed that Bairam Khan was merely using the retreat from Delhi as an excuse to eliminate a rival.

Akbar's army, led by Bairam Khan, met the larger forces of Hemu on 5 November 1556 at the Second Battle of

Panipat, 50 miles (80 km) north of Delhi. The battle was going in Hemu's favour[citation needed] when an arrow

pierced Hemu's eye, rendering him unconscious. The leaderless army soon capitulated and Hemu was captured and executed.[22]

The victory also left Akbar with over 1,500 war elephants which he used to re-engage Sikandar Shah at the siege of Mankot. Sikandar, along with several local chieftains who were assisting him, surrendered and

so was spared death[citation needed]. With this, the whole of Punjab was annexed to the Mughal empire. Before returning to Agra,

Akbar sent a detachment of his army to Jammu, which

defeated the ruler Raja Kapur Chand and captured the kingdom.[23] Between 1558 and 1560, Akbar

further expanded the empire by capturing and annexing the kingdoms of Gwalior, northern Rajputana and Jaunpur.[24]

After a dispute at court, Akbar dismissed Bairam Khan in the spring of 1560 and ordered him to leave on Hajj to Mecca.[24] Bairam

left for Mecca, but on his way was goaded by his opponents to rebel.[22] He was

defeated by the Mughal army in the Punjab and forced to submit. Akbar, however forgave him and gave him the option of either continuing in his court or resuming his pilgrimage, of

which Bairam chose the latter.[25]

Expansion

After dealing with the rebellion of Bairam Khan and establishing his authority, Akbar went on to expand the Mughal

empire by subjugating local chiefs and annexing neighbouring kingdoms.[26] The first major conquest was

of Malwa in 1561, an expedition

that was led by Adham Khan and

carried out with such savage cruelty that it resulted in a backlash from the kingdom enabling its ruler Baz Bahadur to recover the territory while Akbar was dealing with the

rebellion of Bairam Khan.[27] Subsequently, Akbar sent another detachment which captured Malwa in 1562, and Baz Bahadur eventually

surrendered to the Mughals and was made an administrator. Around the same time, the Mughal army also conquered the kingdom of the Gonds, after a fierce battle between the Asaf Khan, the Mughal governor of Allahabad, and Rani Durgavati, the queen of the Gonds.[28] However, Asaf Khan misappropriated most of the wealth plundered from the kingdom, which Akbar

subsequently forced him to restore, apart from installing Durgavati's son as the administrator of the region.[29]

Over the course of the decade following his conquest of Malwa, Akbar brought most of present-day Rajasthan,

Gujarat and Bengal under his control. A major victory in this campaign was the siege of Chittor. The fortress at Chittor, ruled by Maharana Udai Singh, was of

great strategic importance as it lay on the shortest route from Agra to Gujarat and was also considered a key to central Rajasthan. On the advice of his nobles, Udai Singh retired

to the hills, leaving two warriors Jaimal and Patta in charge of the fort.[29]

The Mughal army surrounded the fortress in October 1567 and it fell in February 1568 after a siege of six months. The fort was then stormed by the Mughal forces, and a fierce

resistance was offered by members of the garrison stationed inside, as well as local peasants who came to their assistance. The women committed jauhar while over 30000 men were massacred by the Mughal army.[30][31] It was for the first and last

time that Akbar indulged in carnage of this magnitude. In commemoration of the gallantry of Jaimal and Patta, he ordered that stone statues of them seated on elephants be carved

and erected at the chief gate of the Agra

fort.[29][32] The fortress was completely

destroyed and its gates were carried off to Agra, while the brass candlesticks taken from the Kalika temple after its destruction were given to the shrine of Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer.[30][33]

After Akbar's conquest of Chittor, two major Rajput clans remained opposed to him - the Sisodiyas of Mewar and Hadas of Ranthambore. The latter, reputed to be the most powerful fortress in Rajasthan, was conquered by the Mughal army in

1569, making Akbar the master of almost the whole of Rajputana. As a result, most of the Rajput kings, including those of Bikaner, Bundelkhand and Jaisalmer submitted to Akbar. Only the clans of Mewar continued to resist

Mughal conquest and Akbar had to fight with them from time to time for the greater part of his reign.[29][30] Among the most

prominent of them was Maharana Pratap who declined to accept Akbar's suzerainty and also opposed the marriage etiquette of Rajputs who had been

giving their daughters to Mughals. He renounced all matrimonial alliances with Rajput rulers who had married into the Mughal dynasty, refusing such alliances even with the princes

of Marwar and Amer until they agreed to sever

ties with the Mughals.[34]

Consolidation

Having conquered Rajputana, Akbar turned to Gujarat, whose government was in a state of disarray after the death of its previous ruler, Bahadur Shah. The province was a tempting target as it was a center of world trade, it possessed fertile soil and had highly developed crafts.[35] The province had been occupied by Humayun for a brief period, and prior to that was ruled by the Delhi Sultanate.[29] In 1572, Akbar marched to Ahmedabad, which capitulated without offering resistance. He took Surat by siege, and then crossed the Mahi river and defeated his estranged cousins, the Mirzas, in a hard-fought battle at Sarnal.[35][36] During the campaign, Akbar met a group of Portugese merchants for the first time at Cambay. Having established his authority over Gujarat, Akbar returned to Agra, but Mirza-led rebellions soon broke out. Akbar returned, crossing Rajasthan at great speed on camels and horses, and reached Ahmedabad in eleven days - a journey that normally took six weeks. Akbar's army of 3000 horsemen then defeated the enemy forces numbering 20000 in a decisive victory on September 2, 1573.[35] The conquest of Gujarat marked a significant event of Akbar's reign as it gave the Mughal empire free access to the sea and control over the rich commerce that passed through its ports. The territory and income of the empire were vastly increased.[36] The Mughal army also conquered Bengal (1574), Kabul (1581), Kashmir (1586), and Kandesh (1601), among others. Akbar installed a governor over each of the conquered provinces.

Administration

Taxation

Akbar set about reforming the administration of his empire's land revenue by adopting a system that had been used

by Sher Shah Suri. A

cultivated area was measured and taxed through fixed rates based on the area's crop and productivity. Because taxation rates were fixed on the basis of prices prevailing in the

imperial court, however—which were often higher than those in the countryside[37] -- this placed hardship on the

peasantry. Akbar changed to a decentralised system of annual assessment, but this resulted in corruption among local officials and was abandoned in 1580, to be replaced by a

system called the dahsala.[38] Under the new system, revenue was calculated as one-third of the average produce

of the previous ten years, to be paid to the state in cash. This system was later refined, taking into account local prices, and grouping areas with similar productivity into

assessment circles. Remission was given to peasants when the harvest failed during times of flood or drought.[38] Akbar's

dahsala system is credited to Raja Todar Mal, who also served as a revenue officer under Sher Shah Suri.[39]

Other local methods of assessment continued in some areas. Land which was fallow or uncultivated was charged at concessional rates.[40] Akbar also actively encouraged the improvement and extension of agriculture. Zamindars of every area were required to provide loans and agricultural implements in times of need, to encourage farmers to plow as much land as possible and to sow seeds of superior quality. In turn, the Zamindars were given a hereditary right to collect a share of the produce. Peasants had a hereditary right to cultivate the land as long as they paid the land revenue.

Military organization

Akbar organized his army as well as the nobility by means of a system called the mansabdari. Under this system, each officer in the army was assigned a rank (a mansab), and assigned a number of cavalry that he had to supply to the imperial army.[39] The mansabdars were divided into 33 classes. The top three commanding ranks, ranging from 7000 to 10000 troops, were normally reserved for princes. Other ranks between 10 and 5000 were assigned to other members of the nobility.

The empire's permanent standing army was quite small and the imperial forces mosly consisted of contingents maintained by the

mansabdars.[41] Each mansabdar was required to maintain a certain number of cavalrymen and twice that number of

horses. The number of horses was greater because they had to be rested and rapidly replaced in times of war. Akbar employed strict measures to ensure that the quality of the armed

forces was maintained at a high level; horses were regularly inspected and only Arabian horses were normally employed.[42]

Political government

Akbar's system of central government was based on the system that had evolved since the Delhi Sultanate, but the functions of various departments were carefully reorganised by laying down detailed regulations for their functioning.[citation needed]

-

The revenue department was headed by a wazir, responsible for all finances and management of

jagir and inam lands.[43]

- The head of the military was called the mir bakshi, appointed from among the leading nobles of the court. The mir bakshi was in charge of intelligence gathering, and also made recommendations to the emperor for military appointments and promotions.

- The mir saman was in charge of the imperial household, including the harems, and supervised the functioning of the court and royal bodyguard.

-

The judiciary was a separate organization headed by a chief qazi, who was also responsible for religious endowments.[44]

Akbar departed from the policy of his predecessors in his treatment of the territories he conquered. Previous Mughals extracted a large tribute from these rulers and then leave them to administer their dominions autonomously; Akbar integrated them into his administration, providing them the opportunity to serve as military rulers. He thus simultaneously controlled their power while increasing their prestige as a part of the imperial ruling class.[45] Some of these rulers went on to become the navaratnas in Akbar's court.

Capital of the empire

Akbar was a follower of Salim Chishti, a holy man who lived in the region of Sikri near Agra, who later blessed him with three sons. Believing the neighbourhood to be a lucky one for himself, he had a mosque constructed there for the use of the saint. Subsequently, he celebrated the victories over Chittor and Ranthambore by laying the foundation of a new walled capital, 23 miles (37 km) west of Agra in 1569, which was named Fatehpur ("town of victory") after the conquest of Gujarat in 1573 and subsequently came to be known as Fatehpur Sikri in order to distinguish it from other similarly named towns.[29] Palaces for each of Akbar's senior queens, a huge artificial lake, and sumptuous water-filled courtyards were built there. However, the city was soon abandoned and the capital was moved to Lahore in 1585. The reason may have been that the water supply in Fatehpur Sikri was insufficient or of poor quality. Or, as some historians believe, Akbar had to attend to the northwest areas of his empire and therefore moved his capital northwest. Other sources indicate Akbar simply lost interest in the city[46] or realized it was not militarily defensible. In 1599, Akbar shifted his capital back to Agra from where he reigned until his death.

Matrimonial alliances

Akbar persuaded the Kacchwaha Rajput, Raja Bharmal, of Amber (modern day Jaipur) into accepting a matrimonial alliance for his daughter Jodhaa Bai(but there

is no evidences of Jodhaa Bai.She was Harka Bai who always misiterpreted as Jodhaa Bai). This was the first instance of royal matrimony between Hindu and Muslim

dynasties in India. Jodhaa Bai was

rechristened Mariam-uz-Zamani. After her marriage she was treated as an outcaste by her family and for the rest of her life never visited

Amber.[47] She was not assigned any significant place either in Agra or Delhi, but rather a small village

in the Bharatpur

district.[47] She died in 1623. As a custom Hindus were cremated and never buried;[48] her burial near Agra signifies that she converted to Islam.[49] A mosque was built in her honor by her son Jahangir in Lahore.[50]

Other Rajput kingdoms also established matrimonial alliances with Akbar. The law of Hindu succession has always

been patrimonial, so the Hindu lineage

was not threatened in marrying their princesses for political gain.[citation needed] Rajputs who married

daughters to Mughals still did not treat Mughals as equals, however, they would not dine with Mughals or take Muslim wives.[51]

Two major Rajput clans remained against him, the Sisodiyas of Mewar and Hadas (Chauhans) of Ranthambore. In another turning point of Akbar's reign, Raja Man Singh I of Amber went with Akbar to meet the Hada leader, Surjan Hada, to effect an alliance. Surjan grudgingly accepted an alliance on the condition that Akbar did not marry any of his daughters. Surjan later moved his residence to Varanasi.

Other Rajput nobles did not like the idea of their kings marrying their daughters to Mughals. Rathore Kalyandas

threatened to kill both Mota Raja Udai Singh (of Jodhpur) and Jahangir because Udai Singh had decided to marry his daughter Jodha Bai to Jahangir. Akbar on hearing this ordered imperial forces to

attack Kalyandas at Siwana. Kalyandas died

fighting along with his men and the women of Siwana committed Jauhar.[52]

Entering into alliance with Rajput kingdoms enabled Akbar to extend the border of his Empire to far off regions,

and the Rajputs became the strongest allies of the Mughals. Rajput soldiers fought for the Mughal empire for the next 130 years till its collapse following the death of

Aurangzeb.[citation needed] To foster their compliance, Akbar kept the eldest sons of his Rajput allies as

hostages.[49]

Personality

Akbar's reign was chronicled extensively by his court historian Abul Fazal in the books Akbarnama and Ain-i-akbari. Other contemporary sources of Akbar's reign include the works of Badayuni, Shaikhzada Rashidi and Shaikh Ahmed Sirhindi.

Akbar was an artisan, warrior, artist, armourer, blacksmith, carpenter, emperor, general, inventor, animal trainer (reputedly keeping thousands of hunting cheetahs during his reign and training many himself), lacemaker, technologist and theologian.[12]

Akbar is said to have been a wise ruler and a sound judge of character. His son and heir, Jahangir, in his memoirs, wrote effusive praise of Akbar's character, and dozens of anecdotes to illustrate his virtues.[53] According to Jahangir, Akbar's complexion was like the yellow of wheat. Antoni de Montserrat, the Catalan Jesuit who visited his court described him as plainly white. Akbar was not tall but powerfully built and very agile. He was also noted for various acts of courage. One such incident occurred on his way back from Malwa to Agra when Akbar was 19 years of age.

Akbar rode alone in advance of his escort and was confronted by a tigress who, along with her cubs, came out from

the shrubbery across his path. When the tigress charged the emperor, he was alleged to have dispatched the animal with his sword in a solitary blow. His approaching attendants

found the emperor standing quietly by the side of the dead animal.[54]

Abul Fazal, and even the hostile critic Badayuni, described him as having a commanding personality. He was notable for his command in battle, and, "like Alexander of Macedon, was always ready to risk his life, regardless of political consequences". He often plunged on his horse into the flooded river during the rainy seasons and safely crossed it. He rarely indulged in cruelty and is said to have been affectionate towards his relatives. He pardoned his brother Hakim, who was a repented rebel. But on rare occasions, he dealt cruelly with offenders, such as his maternal uncle Muazzam and his foster-brother Adham Khan.

He is said to have been extremely moderate in his diet. Ain-e-Akbari mentions that during his travels and also while at home, Akbar drank water from the Ganga river, which he called ‘the water of immortality’. Special people were stationed at Sorun and later Haridwar to dispatch water, in sealed jars, to wherever he was stationed.[55] According to Jahangir's memoirs, he was fond of fruits and had little liking for meat, which he stopped eating in his later years. He was more religiously tolerant than many of the Muslim rulers before and after him. Jahangir wrote:

"As in the wide expanse of the Divine compassion there is room for all classes and the followers of all creeds, so... in his dominions, ... there was room for the professors of opposite religions, and for beliefs good and bad, and the road to altercation was closed. Sunnis and Shias met in one mosque, and Franks and Jews in one church, and observed their own forms of worship.[53]"

To defend his stance that speech arose from hearing, he carried out a language deprivation experiment, and had children raised in isolation, not allowed to be spoken to, and pointed

out that as they grew older, they remained mute.[56]

During Akbar's reign, the ongoing process of inter-religious discourse and syncretism resulted in a series of religious attributions to him in

terms of positions of assimilation, doubt or uncertainty, which he either assisted himself or left unchallenged.[57] Such hagiographical accounts of Akbar traversed a wide range of

denominational and sectarian spaces, including several accounts by Parsis, Jains and Jesuit missionaries, apart from contemporary accounts by Brahminical and Muslim orthodoxy.[58] Existing sects and denominations, as well as various religious figures who represented popular worship

felt they had a claim to him. The diversity of these accounts is attributed to the fact that his reign resulted in the formation of a flexible centralised state accompanied by

personal authority and cultural heterogeneity.[57]

Religious policy

Akbar, as well as his mother and other members of his family, are believed to have been Sunni Hanafi Muslims.[59] His early days were spent in

the backdrop of an atmosphere in which liberal sentiments were encouraged and religious narrow-mindednness was frowned upon.[60] From

the fifteenth century, a

number of rulers in various parts of the country adopted a more liberal policy of religious tolerance, attempting to foster communal harmony between Hindus and Muslims.[61] These

sentiments were further encouraged by the teachings of popular saints like Chaitanya, Guru Nanak and Kabir,[60] as well as

the Timurid ethos of religious tolerance that persisted in the polity right from the times of Timur to Humayun, and influenced Akbar's policy of tolerance in matters of religion.[62] Further, his childhood tutors, who included two Irani Shias, were largely above sectarian prejudices, and made a significant contribution to Akbar's

later inclination towards religious tolerance.[62]

One of Akbar's first actions after gaining actual control of the administration was the abolition of jizya, a tax which all non-Muslims were required to pay, in 1562.[60] The tax was reinstated in 1575,[63] a move which has been viewed as being symbolic of vigorous Islamic policy,[64] but was again repealed in 1580.[65] Akbar adopted the Sulh-e-Kul (peace to all) concept of Sufis as official policy and integrated many Hindus into high positions in Mughal Empire and removed restrictions on non-Muslims.

Relation with Hindus

|

|

Akbar's attitudes towards his Hindu subjects were an amalgam of Timurid, Persian and Indian ideas of

sovereignty.[61] The liberal principles of the empire were strengthened by incorporating Hindus into the

nobility.[60] However, historian Dasharatha Sharma states that court histories like the

Akbarnama idealize Akbar's religious tolerance, and give Akbar more credit than he is due.[66]

Akbar in his early years was not only a practising Muslim but is also reported to have had an intolerant attitude

towards Hindus.[67] It was during this period that he boasted of being a great conqueror of Islam to the ruler of Turan, Abdullah Khan, in a letter in 1579,[68] and was also looked upon by orthodox Muslim elements as a devout believer committed to defending the

religion against infidels.[69] However, his attitude towards the Hindu religion and its practices no longer

remained hostile after he began his marriage alliances with Rajput princes. He was also perceived as not being averse to performing Hindu rituals despite his Islamic

beliefs.[69] Hindus boycotted the Vishwanath temple built by Akbar's general Man Singh (which he built after

taking Akbar's permission) because Man Singh's family had marital relations with Akbar.[70] Akbar's Hindu generals could

not construct temples without the emperor's permission. In Bengal, after Man Singh started the construction of a temple in 1595, Akbar ordered him to convert it into a

mosque.[71]

Akbar allowed the conversion of a mosque into Hindu temple at Kurukshetra.[72] He gave two villages for the upkeep of a mosque and a Madrasa which was setup by destroying a Hindu temple.[72] Akbar's army was responsible for the demolition of rich Hindu temples which had gold idols in the

Doab region.[72] He changed name of Prayag to Allahabad pronounced as ilahabad in 1583 as he started a new religion called

Din E ilahi.[73][74]

Relations with Shias and Safavids

|

During the early part of his reign, Akbar adopted an attitude of suppression towards Muslim sects that were condemned by the orthodoxy as heretical.[69] In 1567, on the advice of Shaikh Abdu'n Nabi, he ordered the exhumation of Mir Murtaza Sharifi Shirazi - a Shia buried in Delhi - because of the grave's proximity to that of Amir Khusrau, arguing that a "heretic" could not be buried so close to the grave of a Sunni saint, reflecting a restrictive attitude towards the Shia, which continued to persist till the early 1570s.[75] He suppressed Mahdavism in 1573 during his campaign in Gujarat, in the course of which the Mahdavi leader Miyan Mustafa Bandagi was arrested and brought in chains to the court.[75] However, as Akbar increasingly came under the influence of pantheistic Sufi mysticism from the early 1570s, it caused a great shift in his outlook and culminated in his shift from orthodox Islam as traditionally professed, in favor of a new concept of Islam transcending the limits of religion[75].

Akbar also viewed the Shia Safavid Dynasty in Iran with increasing suspicion and despised the Safavid Abbas I of Persia, and re-captured Kandahar after it was gifted to the Safavid Shah Tahmasp by his father Humayun, (the Safavid's would later capture the Mughal stronghold of Kandahar during the reign of his beloved son Jahangir).

Relations with the Islamic Qazis

In 1580, a rebellion broke out in the eastern part of Akbar's empire, and a number of fatwas, declaring Akbar to be a heretic, were issued by Qadi. Akbar suppressed the rebellion and handed out severe punishments to the Qazi's. In order to further strengthen his position in dealing with the Qazi's, Akbar issued a Mazhar or declaration.[76] The Mahzar asserted that Akbar was the Khalifa of the age, the rank of the Khalifa was higher than that of a Mujtahid, in case of a difference of opinion among the Mujtahids, Akbar could select any one opinion and could also issue decrees which did not go against the nass.[77] Given the prevailing Islamic sectarian conflicts in various parts of the country at that time, it is believed that the Mazhar helped in stabilizing the religious situation in the empire[76] but it made Akbar very powerful above all Islamic religious law and order.

Relations with the Ottoman Empire

During the reign of his father Humayun, the teenage Akbar met the visiting Ottoman Admiral Seydi Ali Reis who was sent by Suleiman the Magnificent, The Admiral is famous today for his books of travel such as the Mirat ul Memalik (Mirror of Countries, 1557) which describes the lands he has seen on his way back from India to Istanbul, and later in 1568 Ottoman Admiral Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis, visited the Mughal ports of Debal, Surat and Janjira during his expedition in the Indian Ocean (see: Indian Ocean campaigns).

In 1577 Akbar sent a very large Hajj caravan, of pilgrims including members of his harem, from Surat led by Mughal Admiral Yahya Saleh, which reached the port of Jeddah and then towards Mecca and Medina in 1577. Four more caravans were sent from 1577 to 1580, with gifts and Sadaqah for the authorities of Mecca and Medina. The pilgrims in these caravans were poor, however, and their stay strained the resources of these cities[78][79]. The Ottoman authorities requested that the pilgrims return home, but the ladies of the harem did not want to leave Hejaz. At length they were forced to return. The Governor of Aden was highly irritated by the huge numbers of pilgrims in 1580 and possibly insulted the Mughals on their way back to India[citation needed]. These events persuaded Akbar to stop sending Hajj caravans and Sadaqat to Mecca and Medina. From 1584 onwards, Akbar seriously considered attacking the Ottoman port of Aden in Yemen with the help of the Portuguese[citation needed]. To forge an alliance, a Mughal envoy was stationed in Goa permanently as of October 1584. In 1587 a Portuguese fleet sent to attack Yemen was routed and defeated by the Ottoman Navy. The Mughal-Portuguese alliance fell through because of the continuing pressure by the Mughal vassals at Janjira[80].

Relation with Christians

Akbar met Portugese Jesuit priests and sent an ambassador to Goa, requesting them to send two missionaries to his

court so that he could understand Christian doctrines better. In response, the Portugese sent Monserrate and Aquiviva who remained at Akbar's court for three

years and left accounts of their visit.[81] In 1603 a written firman was granted at the request of the Christian

priests allowing them to make willing converts.[82] Even armed with the firman, the missionaries however found it extremely difficult to carry

out their work as the Viceroy of Lahore, Qulij Khan, who was a staunch Muslim official, was so harassing in his tactics that many

Christians fled from Lahore and Father Pinheiro

went in fear of death.[83]

Din-i-Ilahi

Akbar was deeply interested in religious and philosophical matters. An orthodox Muslim at the outset, he later

came to be influenced by Sufi

mysticism that was being preached in the country at that time, and moved away from orthodoxy, appointing to his court several talented people with liberal ideas, including Abul

Fazl, Faizi and Birbal. In 1575, he built a hall called the Ibadat Khana ("House of Worship") at

Fatehpur Sikri, to which he invited theologians, mystics and selected courtiers renowned for their intellectual achievements and discussed matters of spirituality with them.[60] These discussions, initially restricted to Muslims, were acrimonious and resulted in the

participants shouting at and abusing each other. Upset by this, Akbar opened the Ibadat Khana to people of all religions as well as atheists, resulting in the scope of the

discussions broadening and extending even into areas such as the validity of the Quran and the nature of God. This shocked the orthodox theologians, who sought to discredit Akbar by circulating rumours of

his desire to forsake Islam.[76]

Akbar's efforts to evolve a meeting point among the representatives of various religions was not very successful,

as each of them attempted to assert the superiority of their respective religions by denouncing other religions. Meanwhile, the debates at the Ibadat Khana grew more acrimonious

and, contrary to their purpose of leading to a better understanding among religions, instead led to greater bitterness among them, resulting to the discontinuance of the debates

by Akbar in 1582.[81] However, his interaction with various religious theologians had convinced

him that despite their differences, all religions had several good practices, which he sought to combine into a new religious movement known as Din-i-Ilahi.[84][85] However, some modern scholars

claim that Akbar did not initiate a new religion and did not use the word Din-i-Ilahi.[86] At about this time, he began

to indicate that he had lost faith in the creed of the prophet of Mecca.[87]

The purported Din-i-Ilahi was more of an ethical system and is said to have prohibited lust, sensuality, slander

and pride, considering them sins. Piety, prudence, abstinence and kindness are the core virtues. The soul is encouraged to purify itself through yearning of God.[88] Celibacy was respected, the slaughter of animals was forbidden and there were no sacred scriptures

or a priestly hierarchy.[89] Though leading Noble of Akbar's court, Aziz Koka, wrote a letter to him from Mecca in 1594 and accused

him that starting of the new cult by Akbar amounted to nothing more than a desire on Akbar's part to portray himself as "a new prophet".[90]

Misconceptions about Akbar propounding a new religion arose because Blochman, translator of Ain-i-Akbari into

English in 1873, erroneously rendered A'in-i Iradat Gazinan which literally means Regulations for those privileged to be his disciple as Ordinances of the

Divine Faith. Also when Blochman translated Badayuni he again mistranslated halqa-i iradat and silsilah-i muridan as Divine Faith and the new

religion respectively when these terms literally stand for circle of disciples.[91] Another mistranslation by

Blochman has altered the meaning of Abul Fazl's words. Fazl says a few were accepted from many into "the circle of discipleship" while Blochman renders it erroneously as

"candidates to the New Faith".[92] At the time of Akbar's death in 1605 there were no signs of discontentment amongst his Muslim subjects

and the impression of even a theologian like Abdu'l Haq was that Akbar remained a Muslim.[3]

Akbarnāma, the Book of Akbar

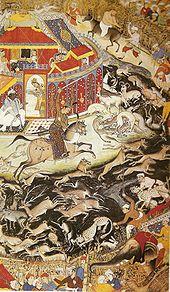

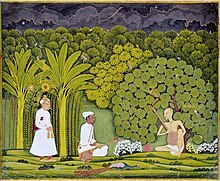

The Akbarnāma (Persian: اکبر نامہ), which

literally means Book of Akbar, is a official biographical account of Akbar, the third Mughal Emperor (r. 1556–1605), written in Persian. It includes vivid and detailed

descriptions of his life and times. [93]

The work was commissioned by Akbar, and written by Abul Fazl, one of the Nine Jewels (Hindi: Navaratnas) of Akbar’s royal court. It is stated that the book took seven years to be completed and the original manuscripts contained a number of paintings supporting the texts, and all the paintings represented the Mughal school of painting, and work of masters of the imperial workshop, including Basawan, whose use of portraiture in its illustrations was an innovation in Indian art [93].

[edit] In popular culture

- In 2008, director Ashutosh Gowariker released a film telling the story of Akbar and his wife Hira Kunwari (known more popularly as Jodha Bai), titled Jodhaa Akbar. Akbar was played by Hrithik Roshan and Jodhaa was played by Aishwarya Rai.

- Akbar was portrayed in the award-winning 1960 Hindi movie Mughal-e-Azam (The great Mughal), in which his character was played by Prithviraj Kapoor.

- Akbar and Birbal were portrayed in the Hindi series Akbar-Birbal aired on Zee TV in late 1990s where Akbar's role was essayed by Vikram Gokhale.

- A television series, called Akbar the Great, directed by Sanjay Khan was aired on DD National in the 1990s.

- A fictionalized Akbar plays an important supporting role in Kim Stanley Robinson's 2002 novel, The Years of Rice and Salt.

- Akbar is also a major character in Salman Rushdie's 2008 novel The Enchantress of Florence.

- Amartya Sen uses Akbar as a prime example in his books The Argumentative Indian and Violence and Identity.

- Bertrice Small is known for incorporating historical figures as primary characters in her romance novels, and Akbar is no exception. He is a prominent figure in two of her novels, and mentioned several times in a third, which takes place after his death. In This Heart of Mine the heroine becomes Akbar's fortieth "wife" for a time, while Wild Jasmine and Darling Jasmine centre around the life of his half-British daughter. His end was an unfortunate luck to both Persian and Indian.

- Akbar is also the AI Personality of India in the renowned game Age of Empires III: The Asian Dynasties.

- The violin concerto nicknamed "Il Grosso Mogul" written by Antonio Vivaldi in the 1720s, and listed in the standard catalogue as RV 208, is considered to be indirectly inspired by Akbar's reign.

- In Kunal Basu's The Miniaturist, the story revolves around a young painter during Akbar's time who paints his own version of the Akbarnama'

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "Jalal-ud-din Mohammed Akbar Biography". BookRags. http://www.bookrags.com/biography/jalal-ud-din-mohammed-akbar/. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ^ a b "Akbar". The South Asian. http://www.the-south-asian.com/Dec2000/Akbar.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ^ a b Habib 1997, p. 96

- ^ a b Conversion of Islamic and Christian dates (Dual) As per the date convertor Akbar's birth date, as per Humayun nama, of 04 Rajab, 949 AH, corresponds to October 14, 1542.

- ^ "Timurid Dynasty". New World Encyclopedia. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Timurid_Dynasty. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "Extant of Empire". http://www.writespirit.net/authors/akbar.

- ^ "The Nine Gems of Akbar". Boloji. http://www.boloji.com/history/022.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ^ a b c Fazl, Abul. Akbarnama Volume II.

- ^ Prasad, Ishwari (1970). The life and times of Humayun. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Ishwari%20Prasad%20life%20and%20times%20of%20humayun&hl=en&lr=&oi=scholart.

- ^ "Akbar". Columbia Encyclopedia. 2008. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-Akbar.html. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ a b Maurice S. Dimand (1953). "Mughal Painting under Akbar the Great". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 12 (2): 46–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3257529.

- ^ a b Habib, Irfan (1992). "Akbar and Technology". Social Scientist 20: 3–15. doi:10.2307/3517712.

- ^ Fazl, Abul. Akbarnama Volume III.

- ^ Part 10:..the birth of Akbar Humayun nama, Columbia University.

- ^ Banjerji, S.K.. Humayun Badshah.

- ^ Fazl, Abul. Akbarnama Volume I.

- ^ "Gurdas". Government of Punjab. http://punjabgovt.nic.in/government/gurdas1.GIF. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ History Gurdaspur district website.

- ^ a b Chandra 2007, p. 226

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 337

- ^ Hoyland, J.S.; Banerjee S.N. (1996). Commentary of Father Monserrate, S.J: On his journey to the court of Akbar, Asean Educational Services Published. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 57. ISBN 8120608070.

- ^ a b Chandra 2007, p. 227

- ^ Habib 1997, p. 3

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 339

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 228

- ^ Habib 1997, p. 4

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 229

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 230

- ^ a b c d e f Chandra 2007, p. 231

- ^ a b c Smith 2002, p. 342

- ^ Chandra, Dr. Satish (2001). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. Har Anand Publications. p. 107. ISBN 8124105227.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 343

- ^ Watson, C.C. (1904). Rajputana District Gazetteers. Scottish Mission Industries Co., Ltd.. p. 17.

-

^ James Tod, Annals and Antiquities of Rajast'han or the Central and

Western Rajpoot States of India, 2 vols. London, Smith, Elder (1829, 1832); New Delhi, Munshiram Publishers, (2001), pp. 83-4. ISBN

8170691281

- ^ a b c Chandra 2007, p. 232

- ^ a b Smith 2002, p. 344

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 233

- ^ a b Chandra 2007, p. 234

- ^ a b Chandra 2007, p. 236

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 235

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 359

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 237

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 240

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 241

- ^ Habib 1997, p. 15

- ^ Petersen, A. (1996). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b Nath 1982, p. 397

- ^ Nath 1982, p. 16

- ^ a b Sarkar 1984, p. 38

- ^ Nath 1982, p. 52

- ^ Sarkar 1984, p. 37

- ^ Alam, Muzaffar; Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1998). The Mughal State, 1526-1750. Oxford University Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780195639056.

- ^ a b Jahangir (1600s). Tuzk-e-Jahangiri (Memoirs of Jahangir).

- ^ Garbe, Richard von (1909). Akbar, Emperor of India. Chicago-The Open Court Publishing Company.

- ^ Hardwar Ain-e-Akbari, by Abul Fazl 'Allami, Volume I, A´I´N 22. The A´bda´r Kha´nah. P 55. Translated from the original persian, by H. Blochmann, and Colonel H. S. Jarrett, Asiatic society of Bengal. Calcutta, 1873 – 1907.

- ^ "1200—1750". University of Hamburg. http://www.sign-lang.uni-hamburg.de/bibweb/Miles/1200-1750.html. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ^ a b Sangari 2007, p. 497

- ^ Sangari 2007, p. 475

- ^ Habib 1997, p. 80

- ^ a b c d e Chandra 2007, p. 253

- ^ a b Chandra 2007, p. 252

- ^ a b Habib 1997, p. 81

- ^ Day, Upendra Nath (1970). The Mughal Government, A.D. 1556-1707. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 134.

- ^ Ali 2006, p. 159

- ^ Dasgupta, Ajit Kumar (1993). History of Indian Economic Thought. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 0415061954.

- ^ Paliwal, Dr. D.L. (Ed.). Maharana Pratap Smriti Granth. Sahitya Sansthan Rajasthan Vidya Peeth. p. 182.

- ^ Habib 1997, p. 84

- ^ Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2005). Mughals and Franks. Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780195668667.

- ^ a b c Habib 1997, p. 85

- ^ Udayakumar, S. P. (2005). Presenting the Past: Anxious History and Ancient Future in Hindutva India. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 99. ISBN 0275972097.

- ^ Forbes, Geraldine; Tomlinson, B.R. (2005). The new Cambridge history of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 0521267285.

- ^ a b c Harbans, Mukhia (2004). The Mughals of India. Blackwell Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 9780631185550.

- ^ Conder, Josiah (1828). The Modern Traveller: a popular description. R.H.Tims. p. 282.

- ^ Deefholts, Margaret; Deefholts, Glenn; Acharya, Quentine (2006). The Way We Were: Anglo-Indian Cronicles. Calcutta Tiljallah Relief Inc. p. 87. ISBN 0975463934.

- ^ a b c Habib 1997, p. 86

- ^ a b c Chandra 2007, p. 254

- ^ Hasan, Saiyid Nurul et al (2005). Religion, state, and society in medieval India: collected works of S. Nurul Hasan. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780195667653.

- ^ Ottoman court chroniclers (1578). Muhimme Defterleri, Vol. 32 f 292 firman 740, Shaban 986.

- ^ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1999). Akbar and his age. Northern Book Centre. p. 218. ISBN 9788172111083.

- ^ Ottoman court chroniclers (1588). Muhimme Defterleri, Vol. 62 f 205 firman 457, Avail Rabiulavval 996.

- ^ a b Chandra 2007, p. 255

- ^ Krishnamurti, R; (1961). Akbar: The Religious Aspect. Faculty of Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. p. 83.

- ^ MacLagan, Edward ; (1932). The Jesuits and the Great Mogul. Burns, Oates & Washbourne. p. 60.

- ^ Chandra 2007, p. 256

- ^ "Din-i Ilahi — Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9030480/Din-i-Ilahi. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ Sharma, Sri Ram (1988). The Religious Policy of the Mughal Emperors. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 42. ISBN 8121503957.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 348

- ^ Roy Choudhury, Makhan Lal (1941), The Din-i-Ilahi, or, The religion of Akbar (3rd ed.), New Delhi: Oriental Reprint (published 1985, 1997), ISBN 8121507774

- ^ Children's Knowledge Bank — Google Books. Books.google.com. http://books.google.com/books?id=0ti8clvedTAC. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ Koka,Aziz (1594). King's College Collection, MS 194. This letter is preserved in Cambridge University Library. p. ff.5b-8b.

- ^ Ali 2006, p. 163

- ^ Ali 2006, p. 164

-

^ a b Illustration from the

Akbarnama: History of Akbar Art Institute of Chicago

References

- Habib, Irfan (1997). Akbar and His India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195637915.

- Nath, R. (1982). History of Mughal Architecture. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 9788170171591.

- Chandra, Satish (2007). History of Medieval India. New Delhi: Orient Longman. ISBN 9788125032267.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1984). A History of Jaipur. Orient Longman. ISBN 8125003339.

- Smith, Vincent A. (2002). The Oxford History of India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195612974.

- Ali, M.A. (2006). Mughal India: Studies in Polity, Ideas, Society and Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195648609.

- Sangari, Kumkum (2007). "Akbar: The Name of a Conjuncture". in Grewal, J.S.. The State and Society in Medieval India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 475–501. ISBN 9780195667202.

Further reading

- Abu al-Fazl ibn Mubarak Akbar-namah Edited with commentary by Muhammad Sadiq Ali (Kanpur-Lucknow: Nawal Kishore) 1881–3 Three Vols. (Persian)

- Abu al-Fazl ibn Mubarak Akbarnamah Edited by Maulavi Abd al-Rahim. Bibliotheca Indica Series (Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal) 1877–1887 Three Vols. (Persian)

- Henry Beveridge (Trans.) The Akbarnama of Ab-ul-Fazl Bibliotheca Indica Series (Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal) 1897 Three Vols.

- Haji Muhammad 'Arif Qandahari Tarikh-i-Akbari (Better known as Tarikh-i-Qandahari) edited & Annotated by Haji Mu'in'd-Din Nadwi, Dr. Azhar 'Ali Dihlawi & Imtiyaz 'Ali 'Arshi (Rampur Raza Library) 1962 (Persian)

-

Akbar, Emperor of India by Richard von Garbe 1857-1927 - (ebook)

-

The Adventures of Akbar by Flora Annie Steel, 1847-1929 -(ebook)

External links

|

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Akbar |

|

|

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Akbar, Jellaladin Mahommed. |

-

Akbar

-

Akbar, Emperor of India by Richard von Garbe' at Project

Gutenberg

-

The Mughals: Akbar

-

The Mughal Emperor Akbar: World of Biography

-

Photos of Akbar The Great's final resting place

|

Akbar the Great

Born: 15 October

1542 Died:

27 October 1605

|

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Preceded by Humayun |

Mughal Emperor 1556-1605 |

Succeeded by Jahangir |

|

||||||||||||||

Personal tools

Toolbox

Languages

-

العربية

-

Aragonés

-

Asturianu

-

Azərbaycan

-

বাংলা

-

Беларуская

-

Bosanski

-

Brezhoneg

-

Български

-

Català

-

Cebuano

-

Česky

-

Cymraeg

-

Dansk

-

Deutsch

-

Ελληνικά

-

Español

-

Esperanto

-

Euskara

-

فارسی

-

Fiji Hindi

-

Français

-

Gaeilge

-

Galego

-

ગુજરાતી

-

한국어

-

Հայերեն

-

हिन्दी

-

Hrvatski

-

Ido

-

Bahasa Indonesia

-

Иронау

-

Íslenska

-

Italiano

-

עברית

-

ಕನ್ನಡ

-

Kiswahili

-

Kurdî / كوردی

-

Latina

-

Latviešu

-

Lietuvių

-

Limburgs

-

Magyar

-

മലയാളം

-

मराठी

-

مصرى

-

Bahasa Melayu

-

Mirandés

-

Монгол

-

Nederlands

-

日

本語

-

Norsk (bokmål)

-

Norsk (nynorsk)

-

O'zbek

-

Pangasinan

-

پنجابی

-

Plattdüütsch

-

Polski

-

Português

-

Română

-

Русский

-

Саха тыла

-

Scots

-

Shqip

-

Sicilianu

-

Simple English

-

Slovenščina

-

Српски / Srpski

-

Srpskohrvatski /

Српскохрватски

-

Suomi

-

Svenska

-

Tagalog

-

தமிழ்

-

తెలుగు

-

ไทย

-

Türkçe

-

Українська

-

اردو

-

Tiếng Việt

-

Võro

-

文 言

-

Winaray

-

Žemaitėška

-

中文

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels