( now the Marriott )

425 Lexington Avenue

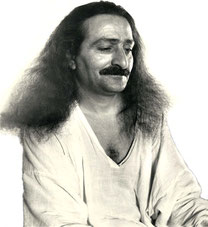

Meher Baba stayed here in 1934

The Shelton Hotel in 1924, and the building today.

By CHRISTOPHER GRAY

Published: March 26, 2009

FEW skyscrapers were as admired in the 1920s as the Shelton Hotel, at Lexington Avenue and 49th Street, now the New York Marriott East Side. Critics agreed that its

picturesque 35-story facade and unusual setback design pointed the way of the future for the skyscraper.

The Shelton, opened in 1924, was built by the architecturally ambitious developer James T. Lee, who was also responsible for two luxurious apartment houses: 998

Fifth Avenue of 1912 and 740 Park Avenue of 1930. He was the grandfather of Jacqueline Kennedy

Onassis, born Jacqueline Lee Bouvier.

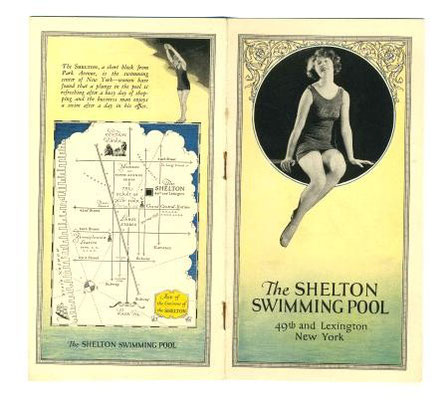

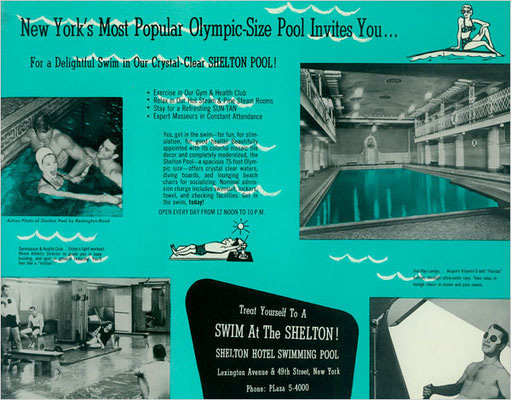

Mr. Lee’s vision was a 1,200-room bachelor hotel with club-type characteristics: a swimming pool, squash courts, billiard rooms, a solarium and an infirmary. The

New York World in 1923 claimed that the Shelton would be the tallest residential building in the world.

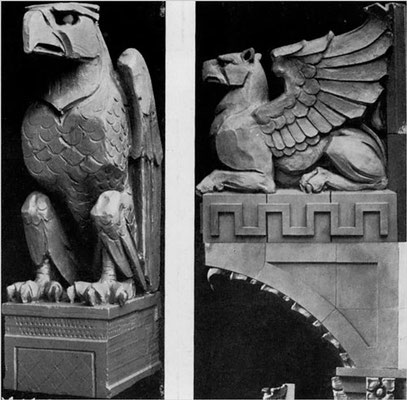

The architect, Arthur Loomis Harmon, covered the mass with irregular yellowy-tan brick, roughened as if centuries old, and for details, drew from Romanesque,

Byzantine, early Christian, Lombard and other styles. But critics were more impressed that it recalled “no definite architectural style of the past,” as the artist Hugh Ferriss put it in The

Christian Science

Monitor in 1923.

To those interested in architecture, however, the significance was its height and how it was used. The Shelton was one of the first buildings to take its form from

a 1916 zoning law that required setbacks at certain heights to insure light and air to the street. That made it quite different from the tall boxy hotels designed before the zoning change, like

the Hotel Pennsylvania, opposite Pennsylvania Station.

“A stately, breath-taking building,” said Helen Bullitt Lowry and William Carter Halbert in The New York Times in 1924. The critic Lewis Mumford, traditionally

stingy with praise, called it “buoyant, mobile, serene, like a Zeppelin under a clear sky” in Commonweal magazine in 1926.

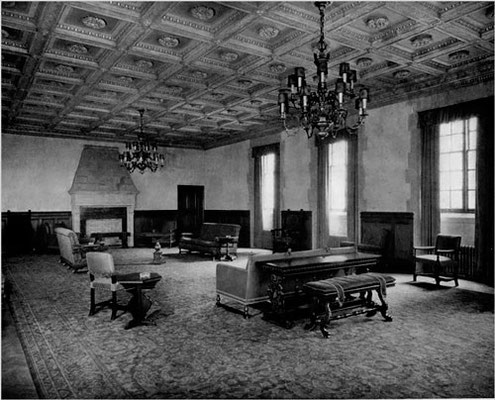

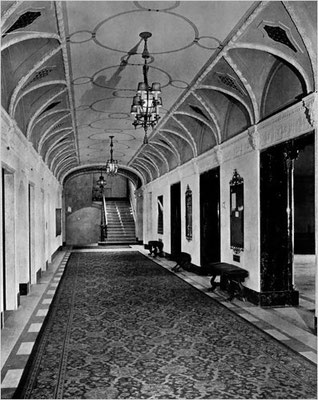

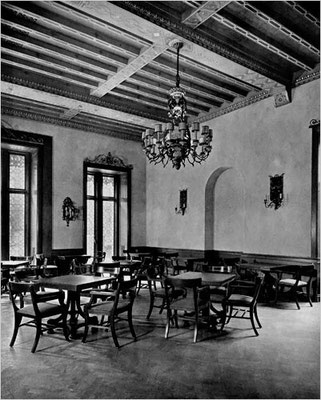

Visionary design has its limits, however, and Mr. Harmon’s interiors appear to have been little different from other giant hotels of the period: great paneled

lounges, a dining room with a beamed ceiling and long groin-vaulted hallways. A third of the rooms had shared baths, which must have posed complications in late 1924, when the Shelton reversed

its men-only policy.

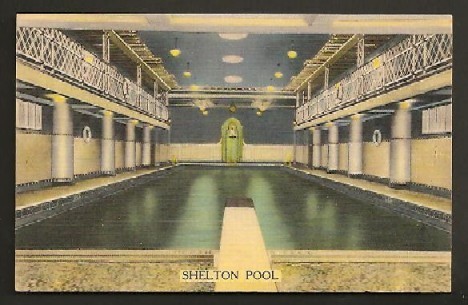

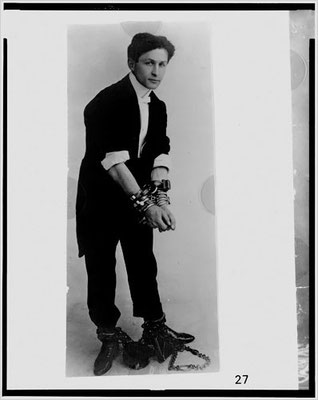

A high gallery ran around the basement pool, which was decorated with polychromed tile. In 1926 the escape artist Harry Houdini was lowered to the

bottom in an airtight coffinlike case, equipped with a telephone in case of trouble. He remained submerged for an hour and a half, stepping out fatigued but alive. He dismissed any suggestion of

magic, saying that a positive attitude was the key. “Anyone can do it,” he told The Times.

The painter Georgia O’Keeffe and the photographer Alfred Stieglitz lived there for several years, taking the hotel as both a subject and as a vantage point from which to paint and photograph the

city.

Gradually the Shelton and other hotels on this section of Lexington Avenue slipped into a sort of half-light, serviceable but worn. By 1974, when the Shelton was

down to 11 permanent residents, it appeared doomed by a new 44-story office building that was to cover the entire block.

The project did not go ahead and the hotel interiors received rough treatment over time. There was very little left by 1990, when Marriott took over operation; the

building is owned by Morgan Stanley.

Michael McMahon, a Marriott spokesman, said Morgan Stanley invested $25 million in room renovations in 2007. “We’ve got great room product now,” he

said.

The architecture and engineering firm Superstructures has a major campaign of exterior repairs under way. Richard Moses, the architect in charge of the project,

says that Mr. Harmon’s high-up details, including heads, masks, griffins and gargoyles, are generally intact, although several that have been particularly beaten up by the elements have been

replaced.

Mr. Moses said that Mr. Harmon made the walls lean in slightly, to give the Shelton a greater solidity. The effect, barely perceptible high up, is evident at ground

level.

The Marriott East Side is down to 646 rooms, and the original interior of the 1924 hotel is down to fragments, like the stair hall to the right of the main lobby.

The squash courts are gone; in their place is an exercise room on the 35th floor with spectacular views all the way round. The hotel has named rooms after Mr. Harmon, Mr. Stieglitz and Miss

O’Keeffe.

Swimming ended years ago, and the space has been split horizontally into three levels. But there is a hint of Houdini in the subbasement: the original tiled pool

ladder at the corner where he was submerged is intact.

James T. Lee continued with his development projects, which included a collaboration on assembling the site for the Chase Manhattan Plaza Building at Pine and

William Streets, built in 1961. He died in 1968.

The Shelton has pretty much disappeared today amid a forest of even taller buildings, and it is hard to imagine the excitement it created in its time.

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels