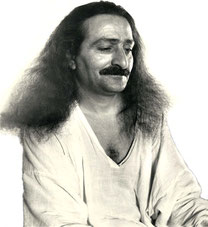

Meher Baba went through this railway station in 1932 on his way across the country

Grand Central Terminal

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Grand Central Terminal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

View inside the Main Concourse, facing east |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Address |

89 East 42nd Street at Park Avenue, New York City, NY 10017 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lines |

Metro-North

Railroad:

Danbury Branch Harlem Line Hudson Line New Canaan Branch |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connections |

New

York City Subway: at Grand Central – 42nd Street MTA New York City Bus: M1, M2, M3, M4, M42, M101, M102, M103, M104, X25 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 44 high-level platforms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 67 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1871 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rebuilt | 1913, 1994 — 2000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessible |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by | Midtown TDR Ventures | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fare zone | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grand Central Terminal (GCT) — sometimes called Grand Central Station or simply Grand Central — is a terminal station at 42nd Street and Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. Built by and named for the New York Central Railroad in the heyday of American long-distance passenger trains, it is the largest train station in the world by number of platforms:[3] 44, with 67 tracks along them. They are on two levels, both below ground, with 41 tracks on the upper level and 26 on the lower, though the total number of tracks along platforms and in rail yards exceeds 100. When the Long Island Rail Road's new station, below the existing levels, opens (see East Side Access), Grand Central will offer a total of 75 tracks and 48 platforms. The terminal covers an area of 48 acres (19 ha).

The terminal serves commuters traveling on the Metro-North Railroad to Westchester, Putnam, and Dutchess counties in New York State, and Fairfield and New Haven counties in Connecticut.

Although the terminal has been properly called "Grand Central Terminal" since 1913, many people continue to refer to it as "Grand Central Station". Technically, "Grand Central Station" is the name of the nearby post office, as well as the name of a previous rail station on the site, and is also used to refer to a New York City subway station at the same location.

[edit] Layout

The tracks are numbered according to their geographic location in the terminal building rather than the trains' destinations, because all of the trains terminate at Grand Central. There are 31 tracks on the upper level in revenue service, numbered from 11 to 42 (tracks 22 and 31 were removed in the late 90's in order to build concourses for Grand Central North, track 12 was removed in order to expand the platform between tracks 11 and 13, and track 14 is only used for loading a garbage train) from the most eastern track to the most western track. On the lower level, there are 26 tracks; they are numbered from 100 to 126, east to west, although only tracks 102-112, and 114-116 are currently used for passenger service. This system makes it easy for passengers to quickly locate where their train is departing from and removes much of the confusion in finding one's train due to the immense size of the terminal. Often, local and off-peak trains will depart from the lower level while express, super-express, and peak trains will depart from the main concourse. Odd numbered tracks will usually be on the east side (right side facing north) of the platform; even numbered tracks on the west side.

Besides train platforms, Grand Central contains restaurants (the most famous of which is the Oyster Bar) and fast food outlets (surrounding the Dining Concourse on the level below the Main Concourse), delis, bakeries, newsstands, a gourmet and fresh food market, an annex of the New York Transit Museum, and more than forty retail stores. Grand Central generally contains only private outlets and small franchises; there are no chain outlets within the complex except for a Starbucks coffee shop and a Rite Aid pharmacy/convenience store.

A "secret" sub-basement known as M42 lies under the Terminal, containing the AC to DC converters used to supply DC traction current to the Terminal. The exact location of M42 remains a closely guarded secret and cannot be found on maps though it has been shown on television, most notably, the History Channel program, Cities of the Underworld and also a National Geographic special. The original rotary converters were not removed in the late 20th century when solid state ones took over their job, and they remain for the purpose of historical record. During World War II, this was one of the most guarded facilities as, if it were sabotaged, troop movement on the Eastern Seaboard would have been halted.[4] Despite it being a secret, Adolf Hitler was aware of this facility and sent two spies to sabotage it. The spies were arrested by the FBI before they could strike. It is said that any unauthorized person entering the facility during the war risked being shot on sight: the rotary converters used at the time could have easily been crippled by a bucket of sand.

From 1924 through 1944 the attic of the east wing contained a 7,000-square-foot art school and gallery space, the Grand Central School of Art.

[edit] Main Concourse

The Main Concourse is the center of Grand Central. The space is cavernous and usually filled with bustling crowds. The ticket booths are here, although many now stand unused or repurposed since the introduction of ticket vending machines. The large American flag was hung in Grand Central Terminal a few days after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center. The main information booth is in the center of the concourse. This is a perennial meeting place, and the four-faced clock on top of the information booth is perhaps the most recognizable icon of Grand Central. Each of the four clock faces is made from opal, and both Sotheby's and Christie's have estimated the value to be between $10 million and $20 million. Within the marble and brass pagoda lies a "secret" door that conceals a spiral staircase leading to the lower level information booth.

Outside the station, the clock in front of the Grand Central facade facing 42nd Street contains the world's largest example of Tiffany glass and is surrounded by sculptures carved by the John Donnelly Company of Minerva, Hercules, and Mercury and designed by French sculptor Jules-Felix Coutan. At the time of its unveiling (1914) this trio considered to be the largest sculptural group in the world. It was 48 feet (14.6 m) high, the clock in the center having a circumference of 13 feet (4 m).

The upper level tracks are reached from the Main Concourse or from various hallways and passages branching off from it.

On the east side of the Main Concourse is a cluster of food purveyor shops which the terminal has designed as Grand Central Market.

[edit] Ceiling

In fall 1998, a 12-year restoration of Grand Central revealed the original luster of the Main Concourse's elaborately decorated astronomical ceiling. The original ceiling, painted in 1912 by French artist Paul César Helleu, was eventually replaced in the late 1930s to correct falling plaster. This new ceiling had been obscured by decades of what people thought was coal and diesel smoke. Spectroscopic examination revealed that it was actually tar and nicotine from tobacco smoke. A single dark patch remains above the Michael Jordan Steakhouse, left untouched by renovators to remind visitors of the grime that once covered the ceiling.

There are two peculiarities to this ceiling: the sky is backwards, and the stars are slightly displaced. One explanation is that the ceiling is based on a medieval manuscript, which visualized the sky as it would look from outside the celestial sphere: this is why the constellations are backwards. Since the celestial sphere is an abstraction (stars are not all at equal distances from Earth), this view does not correspond to the actual view from anywhere in the universe. The reason for the displacement of the stars is that the manuscript showed a (reflected) view of the sky in the Middle Ages, and since then the stars have shifted due to precession of the equinoxes. Most people, however, simply think that Helleu reversed the image by accident. When they learned that the ceiling was painted backwards, the embarrassed Vanderbilt family tried to explain that the ceiling reflected God's view of the sky.

There is a small dark circle in the midst of the stars right above the image of Pisces. In a 1957 attempt to counteract feelings of insecurity spawned by the Soviet launch of Sputnik, Grand Central's Main Concourse played host to an American Redstone missile. With no other way of erecting the missile, the hole had to be cut in order to lift it into place. Historical Preservation dictated that this hole remain (as opposed to being repaired) as a testament to the many uses of the Terminal over the years.

[edit] Dining Concourse and lower level tracks

The Dining Concourse is below the Main Concourse. It contains many fast food outlets and restaurants, including the world-famous Oyster Bar with its Guastavino tile vaults, surrounding central seating and lounge areas and provides access to the lower level tracks. The two levels are connected by numerous stairs, ramps, and escalators.

[edit] Vanderbilt Hall and Campbell Apartment

Vanderbilt Hall, named for the Vanderbilt family who built and owned the station, is just off the Main Concourse. Formerly the main waiting room for the terminal, it is now

used and rented out for various events. The Campbell Apartment is an elegantly restored cocktail lounge, located just south of the 43rd Street/Vanderbilt Avenue entrance, that attracts

a mix of commuters and tourists. It was at one time the office of 1920s tycoon John W. Campbell and is designed to replicate the

galleried hall of a 13th-century Florentine palace.[5]

[edit] Solari display board

The original display board was an electromechanical display used to display the times and track numbers of arriving and departing trains. It contained rows of flip panels to display train information. It became a New York institution, as its many displays would flap simultaneously to reflect changes in train schedules, an indicator of just how busy Grand Central was. A small example of this type now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art as an example of outstanding industrial design.

The flap-board destination sign was replaced with high resolution mosaic LCDs modules [6] manufactured by Solari Udine of Italy: the maker of the original flap boards for train stations and airports. Similar modules are now also used on the trains, both on the sides to display the destination, and on the interior to display the time, next station, calling points and other passenger information.

[edit] Subway station

The subway platforms at Grand Central are reached from the Main Concourse. Built by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) rather than the New York Central Railroad, the subway areas of the station lack the majesty that is present throughout most of the rest of Grand Central, although they are in similar condition to its track levels. The shuttle platforms were originally an express stop on the original IRT subway, opened in 1904. Once the IRT Lexington Avenue Line was extended uptown in 1918, the original tracks were converted to shuttle use. One track remains connected to the downtown Lexington Avenue local track but is not in revenue service. A fire in the 1960s destroyed much of the shuttle station, which has been rebuilt. The only signs of the fire damage are truncated steel beams visible above the platforms.

[edit] Grand Central North

Grand Central North, opened on August 18, 1999, provides access to Grand Central from 45th Street, 47th Street, and 48th Street. It is connected to the Main Concourse through two long hallways, the Northwest Passage (1,000 feet long) and Northeast Passage (1,200 feet long), which run parallel to the tracks on the upper level.[7] Entrances are at the northeast corner of East 47th Street and Madison Avenue (Northwest Passage), northeast corner of East 48th Street and Park Avenue (Northeast Passage), and on the east and west sides of 230 Park Avenue (Helmsley Building) between 45th and 46th Streets. (A fifth entrance will open in September 2011 on the south side of 47th Street between Park and Lexington avenues. [1]. The 47th Street passage provides access to the upper level tracks and the 45th Street passage provides access to the lower level tracks. Elevator access is available to the 47th Street (upper level) passage from street level on the north side of E. 47th Street, between Madison and Vanderbilt Avenues. There is no elevator access to the actual train platforms from Grand Central North; handicapped access is provided through the main terminal.

Nearing the very end of the passages, there is an Arts for Transit mosaic installation by Ellen Driscoll, an artist from Brooklyn.[7]

The entrances to Grand Central North were originally open from 6:30 AM to 9:30 PM Monday through Friday and 9 AM to 9:30 PM on Saturday and Sunday. As of summer 2006, Grand Central North was closed on weekends, with the MTA citing low usage and the need to save money by the shutdown.[8] Prior to the closing, about 6,000 people used Grand Central North on a typical weekend,[9] and about 30,000 on weekdays.

Ideas for a northern entrance to Grand Central were floated around since at least the 1970s. Construction on Grand Central North lasted from 1994 to 1999 and cost $75 million.[7] Delays were attributed to the incomplete nature of the original blueprints of Grand Central and previously undiscovered groundwater underneath East 45th Street. As of 2007, the passages are not air-conditioned.

The passages in the terminal are:

- Metro-North Railroad upper level

- Northwest and Northeast passages

- 47th Street cross-passage

- 45th Street cross-passage

- Metro-North Railroad lower level

[edit] History

Three buildings serving essentially the same function have stood on this site. The original large and imposing scale was intended by the New York Central Railroad to enhance competition and compare favorably in the public eye with the archrival Pennsylvania Railroad and smaller lines.

[edit] Grand Central Depot

Grand Central Depot was designed to bring the trains of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, the New York and Harlem Railroad, and the New York and New Haven Railroad together in one large station. The station was opened in October 1871. The original plan was for the Harlem Railroad to start using it on October 9, 1871 (moving from their 27th Street depot), the New Haven Railroad on October 16, and the Hudson River Railroad on October 23, with the staggering done to minimize confusion. However, the Hudson River Railroad did not move to it until November 1, which puts the other two dates in doubt. The headhouse building containing passenger service areas and railroad offices was an "L" shape with a short leg running east-west on 42nd Street and a long leg running north-south on Vanderbilt Avenue. The train shed, north and east of the head house, had two innovations in U.S. practice: the platforms were elevated to the height of the cars, and the roof was a balloon shed with a clear span over all of the tracks.

The New Haven and New York Central trains were initially in side by side different stations creating chaos in baggage transfer. The combined Grand Central Station service both railroads.

[edit] Grand Central Station

Between 1899 and 1900, the head house was essentially demolished. It was expanded from three to six stories and an entirely new facade put on it, on plans drawn by railroad architect Bradford Gilbert. The train shed was kept. The tracks that had previously continued south of 42nd Street were removed and the train yard reconfigured in an effort to reduce congestion and turn-around time for trains. The reconstructed building was renamed Grand Central Station.

[edit] Grand Central Terminal

[edit] Construction

Between 1903 and 1913, the entire building was torn down in phases and replaced by the current Grand Central Terminal, which was designed by the architectural firms of Reed and Stem and Warren and Wetmore, who entered an agreement to act

as the associated architects of Grand Central Terminal in February 1904. Reed & Stem were responsible for the overall design of the station, Warren and Wetmore added architectural details and

the Beaux-Arts

style. Charles Reed was appointed the chief executive for the collaboration between the two firms, and promptly appointed Alfred T. Fellheimer as head of the combined design team. This work was

accompanied by the electrification of the three railroads using the station and the burial of the approach in the Park Avenue tunnel. The result of this was the

creation of several blocks worth of prime real estate in Manhattan, which were then sold for a large sum of money. The new terminal opened on February 2, 1913.[10]

French sculptor Jules-Alexis Coutan created what was at the time of its unveiling (1914) considered to be the largest sculptural group in the world. It was 48 feet (15 m) high, the clock in the center having a circumference of 13 feet (4.0 m). It depicted Mercury flanked by Hercules and Minerva and was carved by the John Donnelly Company.

[edit] Covering Park Avenue

In order to accommodate ever-growing rail traffic into the restricted Midtown area, William J. Wilgus, chief engineer of the New York Central Railroad took advantage of the recent electrification technology to propose a novel scheme: a bi-level station below ground.

Arriving trains would go underground under Park Avenue, and proceed to an upper-level incoming station if they were mainline trains, or to a lower-level platform if they were suburban trains. In addition, turning loops within the station itself obviated complicated switching moves to bring back the trains to the coach yards for servicing. Departing mainline trains reversed into upper-level platforms in the conventional way.

Burying electric trains underground brought an additional advantage to the railroads: the ability to sell above-ground air rights over the tracks and platforms for real-estate development. With time, all the area around Grand Central saw prestigious apartment and office buildings being erected, which turned the area into the most desirable commercial office district of Manhattan.

The terminal also did away with bifurcating Park Avenue by introducing a "circumferential elevated driveway" that allowed Park Avenue traffic to traverse around the building and over 42nd Street without encumbering nearby streets. The building was also designed to be able to eventually reconnect both segments of 43rd Street by going through the concourse if the City of New York demanded it.

[edit] Terminal City

The construction of Grand Central created a mini-city within New York, including the Commodore Hotel and various office buildings. It spurred construction throughout the neighborhood in the 1920s including the Chrysler Building.

In 1928, the New York Central built its headquarters in a 34-story building (now called the Helmsley Building) straddling Park Avenue on the north side of the Terminal.

There is a secret platform, number 61, under the station.[11] This was used to convey President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his limousine directly into the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, in

order to hide from the public and press his disability, caused by polio. This platform was part of the original design of the Waldorf Astoria. It was mentioned in the New York Times in 1929 but was first used by General

Pershing in 1938.[12]

From 1939 to 1964 CBS Television occupied a large portion of the terminal building, particularly above the main waiting room. The space was used for four studios (41-44), network master control, film projection and recording, and facilities for local station WCBS-TV. In 1958, the first major videotape operations facility in the world opened in a former rehearsal room on the seventh floor of the main terminal building. The facility used fourteen Ampex VR-1000 videotape recorders. The CBS Evening News began its broadcasts there with Douglas Edwards. Many of the historic events during this period, such as John Glenn's Mercury-Atlas 6 space mission, were broadcast from this location. Edward R. Murrow's "See It Now" originated from Grand Central, including his famous broadcasts on Senator Joseph McCarthy. The Murrow broadcasts were recreated in George Clooney's movie "Good Night, and Good Luck." The movie took a number of liberties, in that it was implied that the offices of CBS News and CBS corporate offices were located in the same building as the studios (the news offices were located first in the GCT office building, north of the main terminal, and later in the nearby Graybar Building; corporate offices at the time were at 485 Madison Avenue). The long-running panel show "What's My Line?" was first broadcast from the GCT studios, as were "The Goldbergs" and "Mama". The former studio space is now in use as tennis courts, which are operated by Donald Trump.

[edit] Grand Central Art Galleries

From 1922 to 1958 Grand Central Terminal was the home of the Grand Central Art Galleries, which were established by John Singer Sargent, Edmund Greacen, Walter Leighton Clark, and others.[13] The founders had sought a location in Manhattan that was central and easily accessible, and through the support of Alfred Holland Smith, president of the New York Central Railroad, the top of the terminal was made available. A 10-year lease[14] was signed, and the galleries, together with the railroad company, invested more than $100,000 in preparing the space.[15] The architect was William Adams Delano, best known for designing Yale Divinity School's Sterling Quadrangle.

At their opening the galleries extended over most of the terminal's sixth floor, 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2), and offered eight main exhibition rooms, a foyer gallery, and a reception area.[16] A total of 20 display rooms were to be created for what was intended to be "the largest sales gallery of art in the world."[15] The official opening was March 23, 1923[16], and featured paintings by Sargent, Charles W. Hawthorne, Cecilia Beaux, Wayman Adams, and Ernest Ipsen. Sculptors included Daniel Chester French, Herbert Adams, Robert Aitken, Gutzon Borglum, and Frederic MacMonnies. The event attracted 5,000 people and received a glowing review from the New York Times.

A year after their opening the galleries established the Grand Central School of Art, which occupied 7,000 square feet (650 m2) on the seventh floor of the east wing of

the terminal. The school was directed by Sargent and Daniel Chester French; its first year teachers included painters Jonas Lie and Nicolai Fechin; sculptor Chester Beach; illustrator Dean Cornwell; costume designer Helen Dryden; and muralist Ezra Winter.[17][18]

The Grand Central Art Galleries remained in the terminal until 1958, when they moved to the Biltmore Hotel. When the Biltmore was demolished in 1981 they relocated to 24 West 57th Street.[19] They ceased operations in 1994.

[edit] Proposals for demolition and towers

In 1947, over 65 million people, the equivalent of 40% of the population of the United States, traveled through Grand Central. However, railroads soon fell into a major decline with competition from government subsidized highways and intercity airline traffic.

In 1954, William Zeckendorf proposed replacing Grand Central with an 80-story, 4,800,000-square-foot (446,000 m2) tower, 500 feet (150 m) taller than the Empire State Building. I. M. Pei created a pinched-cylinder design that took the form of a glass cylinder with a wasp waist. The plan was abandoned. In 1955, Erwin S. Wolfson made his first proposal for a tower north of the Terminal replacing the Terminal's six-story office building. A revised Wolfson plan was approved in 1958 and the Pan Am Building (now the MetLife Building) was completed in 1963.

Although the Pan Am Building bought time for the terminal, the New York Central Railroad continued its precipitous decline. In 1968, facing bankruptcy, it merged with the Pennsylvania Railroad to form the Penn Central Railroad. The Pennsylvania Railroad was in its own precipitous decline and in 1964 had demolished the ornate Pennsylvania Station (despite pleas to preserve it) to make way for an office building and the new Madison Square Garden.

In 1968, Penn Central unveiled plans for a tower designed by Marcel Breuer even bigger than the Pan Am Building to be built over Grand Central.

The plans drew huge opposition, most prominently from Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. She said:

- "Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud monuments, until there will be nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children? If they are not inspired by the past of our city, where will they find the strength to fight for her future? Americans care about their past, but for short term gain they ignore it and tear down everything that matters. Maybe… this is the time to take a stand, to reverse the tide, so that we won't all end up in a uniform world of steel and glass boxes."

New York City filed a suit to stop the construction. The resulting case, Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City (1978), was the first time that the Supreme Court ruled on a matter of historic preservation. The Court saved the terminal, holding that New York City's Landmarks Preservation Act did not constitute a "taking" of Penn Central's property under the Fifth Amendment and was a reasonable use of government land-use regulatory power.

Penn Central went into bankruptcy in 1970 in what was then the biggest corporate bankruptcy in American history. Title to Grand Central passed to Penn Central's corporate successor, American

Premier Underwriters (APU) (which in turn was absorbed by American Financial Group). The Metropolitan

Transportation Authority (MTA) signed a 280-year lease in 1994 and began a massive restoration. Midtown TDR Ventures, LLC, an investment group controlled by Argent Ventures LLC, purchased the

station from American Financial in December, 2006.[20] The New York Post reported in July 2007 that TDR is controlled by Argent Ventures.[21]

[edit] Bombing

On September 11, 1976 a group of Croatian nationalists planted a

bomb in Grand Central Station, which was discovered by authorities who unsuccessfully tried to defuse it. The resulting explosion killed a NYPD bomb squad specialist, and wounded more than thirty people.[22] Following the 9/11 attacks, it was briefly thought that the significant date of September 11 signifying an attack against a New York landmark might

indicate Croat nationalist forces at work again.[22]

[edit] Restorations

- Donald Trump

Grand Central both inside and outside and its neighborhood fell on hard times during the financial collapse of its host railroads as well as the near bankruptcy of New York City itself.

In 1974, Donald Trump bought the Commodore Hotel to the east of the terminal for $10 million and then worked out a deal with Jay Pritzker to transform it into one of the first Grand Hyatt hotels. Trump negotiated various tax breaks and in the process agreed to renovate the exterior of the terminal. The complementary masonry from the Commodore was covered with a mirror-glass "slipcover" façade - the masonry still exists underneath. In the same deal, Trump optioned Penn Central's rail yards on the Hudson River between 59th and 72nd Streets that would eventually become Trump Place—the biggest private development in New York City.

The Grand Hyatt opened in 1980 and the neighborhood immediately began a transformation. Trump sold his interest in the hotel for $142 million, establishing him as a big-time player in New York real estate.

- Metro-North

Throughout this period the interior of Grand Central was characterized by huge billboard advertisements, with perhaps the most famous being the giant Kodak Colorama photos running along the entire east side and the Westclox "Big Ben" clock over the south concourse.

Amtrak left the station on April 7, 1991, with the completion of the Empire Connection, which allowed trains from Albany, Toronto, and Montreal to use Penn Station. Previously, travelers would have to change stations via subway, bus, or cab. Since then, Grand Central has exclusively served Metro-North Railroad. Amtrak returned to Grand Central temporarily in October 2008 while construction was being performed on the Empire Connection.

In 1994, the MTA signed a long term lease on the building and began massive renovations. All the billboards were removed. These renovations were mostly finished in 1998, though some of the minor refits (such as the replacement of electromechanical train information displays by the entry of each track with electronic displays) were not completed until 2000. The most striking effect was the restoration of the Main Concourse ceiling, revealing the painted skyscape and constellations. The original baggage room, later converted into retail space and occupied for many years by Chemical Bank, was removed, and replaced with a mirror image of the West Stairs. Although the baggage room had been designed by the original architects, the restoration architects found evidence that a set of stairs mirroring those to the West was originally intended for that space. Other modifications included a complete overhaul of the Terminal's superstructure and the replacement of the electromechanical Omega Board train arrival/departure display with a purely electronic display that was designed to fit into the architecture of the Terminal aesthetically.

The original quarry in Tennessee was located and reopened specifically for the purpose of providing matching stone for not only replacement of damaged stone, but also the new East Staircase. Each piece of new stone was required to carry a marking on it denoting its installation date, and the fact that it was not a part of the original Terminal building.

Ending in 2007, the exterior was once again being cleaned and restored, starting with the west facade on Vanderbilt Avenue and gradually working counterclockwise. The project involved cleaning the facade, rooftop light courts, and statues; filling in cracks, repointing the stones on the facade, restoring the copper roof and the building's cornice, repairing the large windows of the Main Concourse, and removing the remaining blackout paint that was applied to the windows during World War II. The result is a cleaner, more attractive, and structurally sound exterior, and the windows allow much more light into the Main Concourse.

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels