Central Park & 110th (W) Street

20th May, 1932

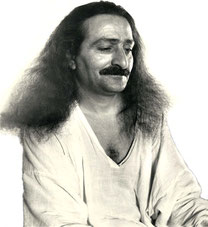

In the evening Baba went for a walk on Broadway in midtown Manhattan. The next day, Baba was driven by Elizabeth through Central Park. This was the first time she had driven Baba. Others had gone in another car, driven by Julian Lamar (the artist). Julian was upset, for someone had broken into his car and stolen his luggage the previous night. He mentioned this incident repeatedly to Baba, who asked, "It wasn't all you had in the world, was it?" Julian admitted it wasn't, and Baba remarked, "I am in you as well as in the thief!"

Lord Meher ; page 1414 -Part A

While they were driving through Central Park, Baba motioned to Elizabeth to stop near the lake at 110th Street. They all got out and walked toward the lake with Baba in the lead. There was no one around except a nurse pushing a baby carriage. After only a glance at the woman, Baba returned to the car. None knew the significance of Baba's stroll that day until a year later when Josephine Grabau was in the hospital and a young woman asked her whose photograph it was by her bed. Jo told her it was Meher Baba, and the woman remarked, "I know it is the same man who looked like Christ, whom I saw walking by the park lake a year ago. I have never forgotten his face."

Baba wished to go to a movie that night on Broadway, which Norina arranged, and a group of eighteen persons went with him. Baba became restless during the film and left in the middle of it. The group followed. Walking through the crowded New York streets, Baba went to another movie theater some blocks away. Along the way, one man stopped and stared straight into Baba's eyes, and then kept turning around to look at him after they had passed on the sidewalk. Perhaps it was for him that Baba had left the theater.

Lord Meher ; page 1414 -Part B

May 20th, 1932

On May 20th, Baba went sightseeing by car around the city with the mandali and saw the Empire State Building. He met many people, but most noteworthy were Elizabeth Patterson's parents, Mr. and Mrs. Simeon B. Chapin, and John Bass, who had been introduced to Baba through Norina. Simeon Chapin was one day to donate several hundred acres of land in South Carolina to be used as a center for the Master's work; and John Bass was to become a lifelong disciple of the Master. In the evening, Baba went for a walk on Broadway in midtown Manhattan.

On May 21st, Baba was driven by Elizabeth Patterson through Central Park. This was the first time she drove for Baba. Julian Lamar drove the car following Baba's. Julian was upset, for someone had broken into his car and stolen his luggage the previous night. He mentioned this incident repeatedly to Baba. Baba asked, "It wasn't all you had in the world, was it?" Julian admitted it wasn't, and Baba remarked, "I am in you as well as in the thief!"

While they were driving through the park, Baba motioned to Elizabeth to stop near the park lake at 110th Street. They all got out and walked toward the lake with Baba in the lead. There was no one around except a nurse pushing a baby carriage. After only a glance at the woman, Baba returned to the car. None knew the significance of Baba's stroll that day until a year later when Josephine Grabau ( Ross ) was in the hospital and a young woman asked her whose photograph it was by her bed. Josephine told her it was Meher Baba, and the woman remarked, "I know it is the same man who looked like Christ, whom I saw walking by the park lake a year ago. I have never forgotten his face."

http://www.centralpark.com/

Strawberry Fields

|

On December 8th, 1980, John Lennon was shot dead as he entered his home at the Dakota Apartment Building at 72nd St. and Central Park West. A long time resident of New York City, Mr. Lennon had taken many walks with his wife and young son through the friendly confines of Central Park. Long a favorite son of his adopted city, John Lennon wasn’t simply New York’s Beatle. He was, for many, the embodiment of the spirit on which city had been built. One half urbane cynic and one half romantic dreamer, he unabashedly embraced the disparate parts which, as every New Yorker knows, combine to form a uniquely gifted, passionate individual.

On March 26, 1981, the city council adopted legislation introduced by then-council member Henry J. Stern on December 18, 1980, which designated the area, stretching from 71st to 74th streets, as Strawberry Fields. His widow, the artist and performer Yoko Ono, later donated $1 million to the Central Park Conservancy to re-landscape and to maintain the 2.5-acre tear-drop-shaped parcel of park landscape. Designed by landscape architect Bruce Kelly the ground breaking ceremony was in March 21, 1984. The name of the site is taken from the Beatle’s song Strawberry Fields Forever and was also, for John, an evocation of an orphanage in Liverpool by the same name. At the center lies the famous Imagine mosaic, donated by the city of Naples. There is also a bronze plaque that lists the 121 countries endorsing Strawberry Fields as a Garden of Peace.

Strawberry Fields opened on October 9, 1985, John's 45th birthday. Every October 9th since then has seen an all day vigil of people of all ages from around the world; fans of his music and believers in his vision.

Location: West Side between 71st and 74th Streets

Details: Strawberry Fields was dedicated by Mayor Edward I. Koch, October 9, 1985, John Lennon's birthday.

History

by Elizabeth Blackmar and Roy Rosenzweig

(please see full credit at the end of this section)

Central Park was the first landscaped public park in the United States. Advocates of creating the park--primarily wealthy

|

merchants and landowners--admired the public grounds of London and Paris and urged that New York needed a comparable facility to establish its international reputation. A public park, they argued, would offer their own families an attractive setting for carriage rides and provide working-class New Yorkers with a healthy alternative to the saloon. After three years of debate over the park site and cost, in 1853 the state legislature authorized the City of New York to use the power of eminent domain to acquire more than 700 acres of land in the center of Manhattan.

An irregular terrain of swamps and bluffs, punctuated by rocky outcroppings, made the land between Fifth and Eighth avenues and 59th and 106th streets undesirable for private development. Creating the park, however, required displacing roughly 1,600 poor residents, including Irish pig farmers and German gardeners, who lived in shanties on the site. At Eighth Avenue and 82nd Street, Seneca Village had been one of the city's most stable African-American settlements, with three churches and a school. The extension of the boundaries to 110th Streetin 1863 brought the park to its current 843 acres.

The question of who should exercise political control of this new kind of public institution was a point of contention throughout the nineteenth century. In appointing the first Central Park Commission (!857-1870), the Republican-dominated state legislature abandoned the principle of "home rule" in order to keep the park out of the hands of locally-elected (and primarily Democratic) office holders. Under the leadership of Andrew Green, the commission became the city's first planning agency and oversaw the laying out of uptown Manhattan as well as the management of the park. After a new citycharter in 1870 restored the park to local control, the mayor appointed park commissioners.

In 1857, the Central Park Commission held the country's first landscape design contest and selected the "Greensward Plan," submitted by Frederick Law Olmsted, the park's superintendent at the time, and Calvert Vaux, an English-born architect and former partner of the popular landscape gardener, Andrew Jackson Downing. The designers sought to create a pastoral landscape in the English romantic tradition. Open rolling meadows contrasted with the picturesque effects of the Ramble and the more formal dress grounds of the Mall (Promenade) and Bethesda Terrace. In order to maintain a feeling of uninterrupted expanse, Olmsted and Vaux sank four Transverse Roads eight feet below the park's surface to carry cross-town traffic. Responding to pressure from local critics, the designers also revised their plan's circulation system to separate carriage drives, pedestrian walks, and equestrian paths. Vaux, assisted by Jacob Wrey Mould, designed more than forty bridges to eliminate grade crossings between the different routes.

The building of Central Park was one of nineteenth-century New York's most massive public works projects. Some 20,000 workers--Yankee engineers, Irish laborers, German gardeners, and native-born stonecutters--reshaped the site's topography to create the pastoral landscape. After blasting out rocky ridges with more gunpowder than was later fired at the Battle of Gettysburg, workers moved nearly 3 million cubic yards of soil and planted more than 270,000 trees and shrubs. The city also built the curvilinear reservoir immediately north of an existing rectangular receiving reservoir. The park first opened for public use in the winter of 1859 when thousands of New Yorkers skated on lakes constructed on the site of former swamps. By 1865, the park received more than seven million visitors a year. The city's wealthiest citizens turned out daily for elaborate late-afternoon carriage parades. Indeed, in the park's first decade more than half of its visitors arrived in carriages, costly vehicles that fewer than five percent of the city's residents could afford to own. Middle-class New Yorkers also flocked to the park for winter skating and summer concerts on Saturday afternoons. Stringent rules governing park use--for example, a ban on group picnics--discouraged many German and Irish New Yorkers from visiting the park in its first decade. Small tradesmen were not allowed to use their commercial wagons for family drives in the park, and only school boys with a note from their principal could play ball on the meadows. New Yorkers repeatedly contested these rules, however, and in the last third of the century the park opened up to more democratic use. In the 1880s, working-class New Yorkers successfully campaigned for concerts on Sunday, their only day of rest. Park commissioners gradually permitted other attractions, from the Carousel and goat rides to tennis on the lawns and bicycling on the drives. The Zoo, first given permanent quarters in 1871, quickly became the park's most popular feature.

In the early twentieth century, with the emergence of immigrant neighborhoods at the park's borders, attendance reached its all time high. Progressive reformers joined many working-class New Yorkers in advocating the introduction of facilities for active recreation. In 1927, August Heckscher donated the first equipped playground, located on the southeastern meadow. When plans were announced to drain the old rectangular reservoir at the park's center, Progressives urged than it be replaced by a sports arena, swimming pool, and playing fields. Other New Yorkers, influenced by the City Beautiful movement, proposed introducing a formal civic plaza and promenade that would connect the two museums at the park's east and west borders. Landscape architects and preservationists campaigned against these design innovations, however, and the site of the reservoir was naturalistically landscaped into the Great Lawn. Such debates over modifications of the Greensward Plan and proper uses of a public park have persisted into the present.

In 1934, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia placed Robert Moses in charge of a new centralized citywide park system. During his twenty-six year regime, Moses introduced many of the facilities advocated by the progressive reformers. With the assistance of federal money during the Depression, Moses built 20 playgrounds on the park's periphery, renovated the Zoo, realigned the drives to accommodate automobiles, added athletic fields to the North Meadow, and expanded recreational programming. In the early 1950s and early 1960s, private benefactors contributed the Wollman Skating Rink, the Lasker Rink and Pool, new boathouses, and the Chess and Checkers house. Moses also introduced permanent ball fields to the Great Lawn for corporate softball and neighborhood little league teams.

In the 1960s, Mayor John Lindsay's two park commissioners, Thomas Hoving and August Heckscher, welcomed "happenings," rock concerts, and be-ins to the park, making it a symbol of both urban revival and the counterculture. In the 1970s, however, severe budget cuts during a fiscal crisis, a long-term decline in maintenance, and the revival of the preservation movement prompted a new approach to managing the park. In 1980, the Central Park Conservancy, a private fundraising body, took charge of restoring features of the Greensward Plan, including the Sheep Meadow, the Bethesda Terrace, and the Belvedere Castle(designed by Vaux and Mould). From 1980 to 1996, the Central Park Conservancy was led by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, who was also appointed the Central Park Administrator; in 1996, Karen Putnam assumed the dual private and public posts. By 1990, the private organization of the Central Park Conservancy contributed more than half the public park's budget and exercised substantial influence on decisions about its future. Central Park, however, continues to be shaped by the public that uses it, from the joggers, disco roller skaters, and softball leagues to bird watchers and nature lovers.

The previous entry on "Central Park" is excerpted from The Encyclopedia of New York City, edited by Kenneth T. Jackson and published by Yale University Press (1995). It is reprinted with the permission of the authors, Elizabeth Blackmar and Roy Rosenzweig. They are also the authors of The Park and the People: A History of Central Park, which was published in 1992 and is available in paperback from Cornell University Press. The Park and the People was awarded a number of prizes, including the Historic Preservation Book Award and the Urban History Association Prize for Best Book in North American Urban History.

Meher Baba's Life & Travels

Meher Baba's Life & Travels